Monday, January 31, 2011

Boss offensive makes progress in Germany

The “secret” behind Germany’s economic recovery

Monday, 31 January 2011

According to the Bundesbank, German GDP grew by 3.6% in 2010. This comes after the steep 4.7% drop in 2009, when the recession hit Germany hard. Unemployment has gone down from the 10.5% peak of 2005 to 7%. It now stands at just under three million. Volkswagen is taking on 3,000 workers, BMW and Daimler 400 each. Lufthansa has announced plans to take on an extra 4,000 staff this year. The same picture can be seen in chemicals, electronics and other industries. When the rest of Europe is facing lay-offs and sluggish growth, what is different about Germany?

Within the European Union also German exports of cars, machine tools, chemicals, electronic goods have been dominating the market. The weaker economies like Italy, Greece, Spain, have all been losing out, seeing their own unemployment levels surge.

The irony of all this is the following: German banks have lent money to these countries over the past decade, which has been used to provide credit that has ended up being used to buy German goods. Now that this piling up of credit has turned into the deepest financial crisis since 1929, the German capitalists are complaining that Germany has been called on to bail them out because of their national debts.

Sooner or later this is going to provoke a financial crisis in Germany itself. But for now Germany is exporting its way out of the crisis. This, of course, means also exporting unemployment and increasing the problems of the weaker European economies.

Why is Germany more competitive?

The question one has to ask is: why is Germany more competitive? The answer to that is to be found in the power of its industrial base. In countries like Britain it became fashionable in the past decades to praise the banking and services sector of the economy. London was a key financial centre, where much of the money made elsewhere was being banked and invested in all kinds of financial schemes. Germany, on the other hand, maintained a much stronger manufacturing sector.

The boom of the past 20 years or so led investors to believe they could make money from money, without going through the troublesome task of actually investing in the production of real value, i.e. goods! This brings us to a basic postulate of Marxist economic theory, and that is that value can only be created by putting human labour power to work in the production of goods that are required by humans. Pushing up the price of a house as a result of a bubble doesn’t actually increase the real value of the house. It still remains a house, in which only one family can live. Sooner or later these bubbles must burst and the nominal price must come into line with the real underlying value. This has partially been achieved, but more is to come as house prices will inevitably come down further in the coming years.

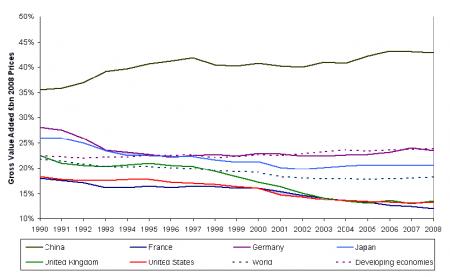

Returning to Germany, we see an economy where manufacturing is a much bigger part of overall GDP. The table below shows manufacturing as a percentage of GDP in China, France, Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States. China clearly outflanks all the other major powers, and here lies the secret to its success. Germany comes second. In the last 20 years manufacturing as a percentage of GDP in Germany has remained close to 25%. In Britain it has gone down from around 22% to around 13%.

Manufacturing as a percentage of GDP globally and across comparator countries

If we look at productivity – measured as gross added value per hour in the production of commercial goods between the years 1997 and 2007 in Germany, France, Italy, Spain, Britain and Japan, we see that only in Germany is there a net growth. [Source: EU, Klems]. According to an article, Why Germany's Top Manufacturers Succeed, published by Germany Trade & Invest, the foreign trade and inward investment agency of the Federal Republic of Germany:

“...German competition winners... have bucked the expected trend. They've defied experts who believed that services, rather than manufacturing, were the way of the future for Germany. Moreover, they've contradicted the widely held assumption that outsourcing production overseas is an ideal cost-saving strategy. In no other industrialized country is manufacturing more essential than in Germany. In 2008, twenty-three percent of gross value added in Germany came from the manufacturing sector; compared to 13.3 percent in the USA and significantly less in Great Britain and France.”

Apart from the boasting on the part of a German government agency (as it conveniently ignores China), this gives a good picture of the situation. German manufacturing is stronger than that of its competitors, and the key question is growth in productivity. But how has this been achieved, and more importantly what has it meant for German workers?

The fact is that the German workers who produce all these competitive industrial goods, cars, chemical goods and electronics, have been under the cosh in terms of the real value of their wages for about a decade now. And this is thanks partially to the role of the trade unions who have wholeheartedly embraced “mitbestimmung”, co-determination or so-called workers’ participation. This is a system which is supposed to allow the workers a say in the running of factories. In reality it is a way of getting workers to accept what the bosses want, but make them feel they are part of the decision-making process.

Bosses’ offensive against the workers

How has it been applied during the recent recession? For the past three years, for example, the wages of the 750,000 German car workers have been frozen. The bosses and the trade unions – who have a representative on the board of managers – agreed to hold back wage increases and to cut hours. In 2009, when the recession hit home, over one million workers were on “short time” work, known in German as Kurzarbeit, of two or three day weeks and on 70% of their wages. At Opel wages have been frozen for the whole of 2011 and holiday pay at Christmas and in the summer has been halved.

In the period 1977 to 1997 productivity in Germany grew by an average of 3.2% a year, whereas hourly wages grew at the rate of 4.25% per year. In fact hidden behind the image of an industrial powerhouse, for a period of around 20 years, as the Financial Times explains, was the fact that, “growth in output per person [was] seven percentage points lower than the UK from reunification in 1990 until the financial crisis.”

All this was clearly unacceptable for the bosses who went on an offensive against the German workers demanding “sacrifices” which the trade union leaders agreed to. In the past ten years wage demands have been very much on the moderate side. This explains why in the past five years there has been a very big increase in productivity of labour in terms of cost to output ratio.

If we look at real wages per worker, cost of labour per unit of production and hourly productivity we get a clear picture of what has happened. Between 1997 and 2010 real wages went down by 10% and hourly productivity rose by around 8%, resulting in an overall reduction of 25% in the unitary cost of labour. [Source: EU Commission]. According to the Global Wage Report recently published by the International Labour Organisation, German workers’ wages over the past decade have shrunk more than in any other industrialised country.

Added to this has been the increasing “flexibility of labour”. The number of workers on permanent contracts has fallen in the recent period. In 2011 for the first time in its history there will be over one million temporary workers in Germany. This means German capitalists can take on workers when the economy is growing and dump them in times of recession. And the wages earned by these workers – known as the “€400 jobs”, are much lower than those of workers on permanent contracts.

Translated into simple language, all this means that the bosses have managed to squeeze down real wages while at the same time getting more production out of each worker per hour. This is the “secret” to German industry’s increased productivity. Thus it can outcompete its rivals, but at the cost of holding down real wages for German workers. This means that its own domestic market, although big, is not big enough to absorb the immense productive capacity of German industry; hence, the need for Germany to export more.

In the recent period this process was facilitated by the 2009 recession. In fact in that year trade union militancy was at a low ebb, as workers kept their head down waiting for the storm to pass. An indicator of the mood that existed in 2009 is the fact that that year saw the lowest number of day lost through sickness since the health ministry began collecting data on sick days in 1970. As Joachim Moeller of Nuremburg's Institute for Employment Research, explained: “In times of economic crisis, the number of sick days taken tends to go down,” He added that workers in times of recession are often afraid they may lose their jobs and go to work even when they are sick.

Mood beginning to change

Now, however, things are starting to change. Marxists understand that there is no direct correlation between the economic cycle and class struggle; put more simply, recessions do not automatically provoke class struggle and booms do not automatically calm class conflict. The German workers have made many “sacrifices” in the recent period. This they did because the bosses and the trade union leaders sold them the story that such sacrifices were for the good of all and that this was the only way to get the economy moving again.

Well, the economy is moving, production is up, and exports are going at full blast. Last year German growth was its highest since 1991 and German business “confidence” is high. So when are the workers going to be rewarded for their sacrifices, not to speak of the millions of poor in Germany? The position of the poor is in fact a dire one. Seven million Germans, on top of the three million unemployed, live on some form of benefit. At the end of 2010 Merkel gave these poor a paltry 5 euros increase, bringing their monthly cheque from 359 euros to 364, “an insult” as the former leader of the Die Linke, Oskar Lafontaine described it. This “reserve army of labour” has been used to push down wages in general, threatening the workers that unless they accepted wage cuts and worse conditions they could easily join this army of unemployed.

However, this nice cosy set up – for the bosses that is – cannot last forever. There is a limit to what workers can take. And now the German workers are about to present the bill. A militant mood is beginning to develop now and this is reflected within the trade unions who are about to enter into a period of wage negotiations. In the coming months collective bargaining agreements expire in the chemical industry, at Volkswagen, for shop, hotel and insurance workers. In December the collective bargaining agreement for the regional government workers had already expired. The total number of workers whose labour contracts are up for renewal is 7.5 million.

The trade union that organises the regional government workers has already put in a demand for a 5% wage increase, when official inflation figures are hovering around the 2% mark. The unions are seeking to claw back some of what was lost in the recent period.

A German economist, Gustav Horn, considered “close to the trade unions” expects wages to grow on average by 1.8% in 2011, still below the rate of inflation, but in those industries where labour contracts are to be renewed this year he sees wages going up by 3 to 4%.

The militant mood of the workers can be seen in the steel industry where the IG Metall in October managed to win a significant concession: temporary workers are to receive the same wages as permanent workers, while the DGB trade union federation has been demanding a minimum wage for some time. At Volkswagen, where the labour contract expires at the end of this month, the trade unions have put in a demand for a 6 percent wage increase, while the union Ver.di has called for a 6.5 percent rise for telecommunications employees. The IG BCE union recently demanded a rise of at least 6% for Germany’s 550,000 chemical industry workers.

The boom in Germany is bringing with it growing exports and rising profits. Employment is growing as companies take on more workers to meet growing demand. In these conditions the confidence of the German workers is growing. Those same workers, who were forced to keep their heads down in times of recession and growing unemployment, will now feel their time has come. They will present the bill to the capitalists and demand their share. This is a recipe for class struggle in Germany. And we can confidently predict that the German working class in the coming period will join their workers across Europe and beyond in the fightback.

Texts “as fantasmagorias bearing witness to the hidden truth about a society”

The Politics of Literature by Jacques Rancière

Posted on 31,Jan 2011

The Politics of Literature

by Jacques Rancière

(translated by Julie Rose)

Polity;

Paperback, 206 pages;

ISBN: 978 0 745 64531 5

Price: £17.99

Adam Guy

Jacques Rancière has been active since 1965, when, aged 25, he wrote part of Louis Althusser’s Lire le Capital (Reading Capital). It has only been in the past ten years, though, that his reputation in the English-speaking world has seriously taken off. Whether this is because his time has come, or simply because he fits the profile required by an expanding demand for continental philosophy in English-language editions (one major beneficiary of this, Slavoj Žižek, provides an Afterword for Continuum’s edition of The Politics of Aesthetics), remains to be seen. Julie Rose’s translation of Politique de la Littérature, a collection of ten essays, is the latest to join the fray.

The key concept here is, unsurprisingly, Rancière’s definition of Literature, which runs consistently throughout the book. Literature for Rancière is not just all and any literary text ever, but instead a particular invention of the 19th century and a product brought to perfection by Flaubert, who features in this book more than anyone else. In Rancière’s view, before the radical break of Literature, texts were caught up in a circuit of logic, order, and (behind this) domination: “a complete hierarchical system of the affinity between characters, situations, and forms of expression”. Each social class had a genre and a mode of speech, and so-called literary texts were merely a way of confirming this to people.

Subsequently, the revolution of Literature as such is the revolution of “the reign of writing, of speech circulating outside of any determined relationship of address”. In Literature, as is evident to any reader of Balzac, Flaubert, or Proust, the trivial detail rules, and the reason for this means everything:

Everything talks. Meanings are no longer established according to the plausibility of intentions and expressions. But also, everything talks equally. No one thing talks more than any other thing. The abundant difference of signs is then lost in the equal insignificance of states of things. The written sign turns into any old bit of garbage or into sheer difference in intensity – to the point where nothing more can be read except the indifferent vibration of atoms in their random variations.

The Politics of Literature feeds all sorts through this definition, so that not just Flaubert and Proust, but also Wordsworth, Tolstoy, Mallarmé, Freud, and the Modern Notion of History are seen as symptoms of the radical shift to the regime of Literature. For the Literary Studies nerd (at whom this collection must at least in part be aimed), the most thrilling example of this comes at the times when Rancière shows how the major mode of reading texts taught worldwide in university Literature departments is also folded within Literature’s paradigm shift. Any Lit student will be familiar with the idea of “analys[ing] prosaic realities” gestured towards in texts “as fantasmagorias bearing witness to the hidden truth about a society”, as “tell[ing] the truth about the surface by tunnelling into the depths and then formulating the unconscious social text that is to be deciphered there”. This is the standard historicist’s method, the way people have dug out the colonial exploitation propping up Mansfield Park, or the shifting notions of property rights hiding behind Wuthering Heights. Rancière argues, though, that Literature got there first, that Literature itself “provided the conceptual schemas with which people claim to be demystifying it”; the writer like Flaubert was always already “the archaeologist or geologist who gets the mute witnesses of common history to speak”.

What this gymnastic twist also shows is the major structuring principle in Rancière’s thought: the dialectic. In this sense, the book’s one slight anomaly, the 1979 essay ‘The Gay Science of Bertolt Brecht’ (the only piece in the collection written before 1997), provides an illuminating introduction to Rancière’s thought. The essay stands here as a kind of sparring match where Rancière pits himself against another master of the Marxist dialectic. In true dialectical style, no one really wins, but everyone goes home happy realising that there was a broader encompassing term that better conceptualised their battle. Anyone at all familiar with Slavoj Žižek or Fredric Jameson will be perfectly at home here.

Having talked about Rancière’s concept of Literature and come to the dialectic, surely here is the point to mention the Politics of that Literature. Rancière’s ideas about everything talking, of a new democracy of literary objects, of revolutions and epistemological breaks already suggest a Politics, and it is clear that his interest in Flaubert, et. al. lies in their emancipatory potential. However, to some extent, the Politics stays in the background in this collection. The Politics of Literature is better seen as a small part carved out of a broader whole, that of Rancière’s entire output, which puts forward a bona fide left-wing project with real roots in actions rather than mere ideas.

There are other sides of Rancière shown here too. For example, flashes appear throughout the volume of a true philosopher of the multiple, a philosopher of supplement and excess rather than lack, and also one with a real interest in the idea of the Event. This is brought to the fore in the forbidding final essay on another more recent discovery of English-language philosophy publishers, Alain Badiou. But perhaps the ultimate value of The Politics of Literature is its status as a volume of literary theory, pure and simple. One major sign of this is the fact that, whereas many continental philosophers see Plato as the be-all-and-end-all of early philosophy, Rancière takes constant interest in Aristotle, and especially the Aristotle of the Poetics.

For some, the term “French philosopher” is cause to reach for one’s revolver. But the fact that the very idea of a poetics is what seems to engage Rancière most here should attract even the hardiest detractor. It is refreshing to see that, while so many writers on the subject believe that any discussion of literature must necessarily cede to a discussion of history or metaphysics, Rancière still believes that a notion of poetics can be found, and that literature in itself can still be spoken about.

US imperialism as a dying force, incapable of being reformed, because it owes its existence to slavery and genocide

International Conference on White Solidarity with Black Power wins allies and resources for the African national liberation struggle.

5360864183_41470557ed.jpg

The APSC was founded in 1976 by the African People's Socialist Party to organize for reparations to Africa and African people in the form of material solidarity from the North American (white) community.

Comrades from San Diego and Oakland, CA; Athens and Columbus, OH; Minneapolis, MN; Chicago, IL; New York City, NY; Providence, RI; Philadelphia, PA; Boston, MA; and Miami, Palm Harbor, Brandon, and Sarasota, FL engaged in three days of rigorous discussion and political education meant to deepen white people's understanding of our key role in the revolutionary struggle for African liberation.

The conference served as APSC’s annual national Plenary, which is mandated by the documents coming out of the African People’s Socialist Party USA (APSP USA) Fifth Congress held last July in Washington, DC. The Party emerged from that historic event as the most acknowledged leading force of the African Liberation Movement. And the Fifth Congress resolved that APSC must be built to meet the demands of the African Revolution in this period of the Final Offensive Against Imperialism.

“The African Revolution is evolution, because it will bring humanity to a higher level,” said APSC Chairwoman Penny Hess in her opening remarks. Hess characterized US imperialism as a dying force, incapable of being reformed, because it owes its existence to slavery and genocide.

Historically, white left forces have resorted to opportunism and charity politics when faced with the revolutionary struggles of African people, but APSC avoids opportunism by working directly under the leadership of the African People's Socialist Party.

Chairwoman Hess explained the significance of this principled relationship: “When left to our own devices, we [North Americans] will always come up in our own interest. Organizing in material solidarity under the leadership of the APSP overturns the economic basis of our opportunism.”

Chairman Omali Yeshitela led a three-hour workshop on "A World Without Borders," in which he explained the controversial issue of "nation-building" by colonized peoples as a necessary pre-requisite for successful anti-imperialist struggle.

» See video highlights from the conference - http://www.apscuhuru.org/events/2011_conference/videos.xhtml

Chairman Omali brilliantly showed how the European or white nation was forged at the expense of the African nation and that it will be the emergence of the movement to unite and liberate Africa and African people everywhere that will bring about the destruction of the European nation.

As the Chairman stated, “The European nation was born as a bourgeois nation, a capitalist nation, through exploitation and the expropriation of value from everybody else.

Therefore, the fundamental task of the African revolutionary is the liberation and consolidation of the African nation, which will not be born as a bourgeois nation, but will be born in contention with the imperialist bourgeois nation and born as a workers' or proletarian nation."

Reading aloud from the Political Report to the Fifth Congress, the Chairman explained the concept of a world without borders: “African people have to resist the imperialist bourgeoisie as a people. Our assumption of consolidated nationhood will function to destroy the bourgeois nation. Thus, the rise of revolutionary worker nation-states destroy the material basis for the existence of nations and borders that function to distinguish and separate one people from another.”

The Chairman noted the national unity of African people everywhere in music, style, culture, dress and ability to understand each other regardless of the language imposed on them.

He said, “The truth of the matter is there is a sense of sameness among black people all around the world. Even people who call themselves different things. Africans in Haiti were upset when they saw Katrina. Africans I knew from Ethiopia who were meeting in Berlin were upset by when they saw Katrina. And Africans all around the world were upset about Haiti, pissed off about Haiti, hate what the Red Cross is doing in Haiti, hate what Clinton is doing in Haiti, really upset about Haiti. There is a sense of sameness among black people in the world - that is just a fact.”

Diop Olugbala, President of the International People's Democratic Uhuru Movement (InPDUM), spoke on the history of the African People's Socialist Party from its origins in the Black Revolution of the 1960s.

A presentation called “Uhuru Solidarity on the Move” looked back on the past year of activity in the Uhuru Solidarity Movement and the expansion of its national leadership body.

Ironiff Ifoma, Director of Economic Development and Finance for the APSP-USA, gave a presentation called “Creating an African Internationalist Economy,” on the current period of tremendous growth for her department and the need to “build contending power to bring the masses into the embrace of the Party” by recreating the culture of self-reliance in the African community.

Chairwoman Hess presented on the history of ideological development within APSC as its leadership struggled against opportunism and subjectivism before temporarily disbanding in 1981.

When APSC reformed, with Hess as its chairperson, the political line of African Internationalism had been consolidated around the question of reparations from the white community as a revolutionary and principled stance.

“Reparations is our revolutionary work,” said Hess.

An event held on the evening of January 10 called “Prisons, the Drug War and African Resistance” included Chairman Omali Yeshitela, Penny Hess, Diop Olugbala and Mwamba Yeshitela, a leader in the campaign for African youth resistance.

Using a slideshow presentation, Chairwoman Hess juxtaposed images to illustrate the parallel conditions of military occupation in Afghanistan and police occupation in oppressed African communities in North America.

President Diop Olugbala discussed his recent work in Philadelphia where he and other InPDUM forces have been leading a campaign to organize African youth into the Junta of Militant Organizations (JOMO), the African youth resistance wing of InPDUM.

Mwamba Yeshitela gave a compelling, informative account of his real-life experiences as a young African facing colonial conditions of poverty and police containment on the south side of St. Petersburg.

On the third day of the conference, APSC elected the new National Central Committee (NCC). NCC members include:

* Penny Hess, National Chairperson

* Alison Hoehne, National Secretary General

* Kitty Reilly, National Director of Reparations and Economic Development

* Lisa Watson, National Director of Agitation and Propaganda

* Maureen Wagener, National Director of Uhuru Foods

* Stephanie Midler, National Director of the Uhuru Solidarity Movement and Southeast Regional Representative

* Joel Hamburger, National Representative of Uhuru Furniture

* Wendy Snyder, West Regional Representative

* Harris Daniels, Northeast Regional Representative

APSC also adopted its Supplement to the Constitution of the African People's Socialist Party USA.

The conference gained several new members, raised resources for the work of the APSP and passed many resolutions, including resolutions to build a movement to stop the US war against the African community and defend the right of African people resist, to build the Uhuru Solidarity Movement nationally among North Americans and to transform Uhuru Foods into an even stronger institution of reparations and material solidarity to the African Liberation Movement.

For more information on APSC and how to join, visit the APSC website at http://www.apscuhuru.org.

The 7 Habits of Highly Effective Communists

Zhou Enlai

Guidelines for Myself

Written: March 18, 1943

First Published: 1981 (English translation)

Source: Selected Works of Zhou Enlai, Volume 1

Online Version: Zhou Enlai Internet Archive, March 2003

Transcribed/HTML Markup: Roland Ferguson

1. Study diligently, grasp essentials, concentrate on one subject rather than seeking superficial knowledge of many.

2. Work hard and have a plan, a focus and a method.

3. Combine study with work and keep them in proper balance according to time, place and circumstances; take care to review and systemize; discover and create.

4. On the basis of principles, resolutely combat all incorrect ideology in others as well as in myself.

5. Insofar as possible, make the most of my strengths and take concrete steps to overcome my weaknesses.

6. Never become alienated from the masses; learn from them and help them. Lead a collective life, inquire into the concerns of the people around you, study their problems their problems and abide by the rules of discipline.

7. Keep fit and lead a reasonable regular life. This is the material basis for self-improvement.

Follow the bouncing ball

The Ballad of English Literature by Terry Eagleton

Chaucer was a class traitor

Shakespeare hated the mob

Donne sold out a bit later

Sidney was a nob

Marlowe was an elitist

Ben Johnson was much the same

Bunyan was a defeatist

Dryden played the game

There's a sniff of reaction

About Alexander Pope

Sam Johnson was a Tory

And Walter Scott a dope

Coleridge was a right winger

Keats was lower middle class

Wordsworth was a cringer

But William Blake was a gas

Dickens was a reformist

Tennyson was a blue

Disraeli was mostly pissed

And nothing that Trollope said was true

Willy Yeats was a fascist

So were Eliot and Pound

Lawrence was a sexist

Virginia Woolf was unsound

There are only three names

To be plucked from this dismal set

Milton Blake and Shelley

Will smash the ruling class yet

Milton Blake and Shelley

Will smash the ruling class yet.

--

in Against the Grain, Essays by Terry Eagleton, Verso Books

Stalinisn is revisionism

Marxism and theoretical overkill

Mike Macnair reviews Jairus Banaji's 'History as theory: essays on modes of production and exploitation' Historical Materialism books series, Vol 25, Leiden, 2010, pp406, £81

In March 2010 the Indian novelist, Arundhati Roy, published in the journal Outlook India a substantial and sympathetic report of the activities of the Naxalite (Indian Maoist) guerrillas in Chattisgarh state in eastern India.[1] Roy’s report has been very widely circulated on the web. It has also been the subject of furious attacks from Indian establishment politicians and the threat of prosecution under ‘anti-terrorism’ laws (though more serious threats to prosecute Roy, this time for sedition under the Indian penal code, have been made in relation to another article which supported the secession of Kashmir).[2]

Shortly after Roy’s article was published, leftist and academic Jairus Banaji posted a short sharp critique of it on the Indian political blog Kafila. If Roy’s original article was savaged by the Indian political establishment, comrade Banaji’s critique has given rise to almost equally sharp polemics on the Indian left.[3] Banaji has elaborated his critique in a substantial article, ‘The ironies of Indian Maoism’ in the autumn 2010 issue of the Socialist Workers Party’s theoretical journal, International Socialism.

Why is this current political debate relevant to History as theory, Banaji’s collection of essays written between 1976 and 2009, mainly on the problems of Marxist interpretation of ancient and medieval history? The answer is that Banaji’s theoretical arguments are in the last analysis targeted on those used by Indian ‘official communists’ and Maoists in support of their respective political lines.

‘Official communists’ argue, the world over, for a strategic alliance between the working class movement and sections of the bourgeoisie. In the old central imperialist countries this is usually presented as an ‘anti-monopoly’ alliance. In the countries which were formerly colonised, in contrast, the argument is that capitalism is not fully developed, because of colonial or neo-colonial subordination: there are significant ‘survivals of pre-capitalist relations of production’. ‘Official communists’ claim that it is therefore necessary to ally with the ‘national’ bourgeoisie against imperialism and/or with the ‘democratic’ bourgeoisie against the old landlords and similar classes to ‘complete the bourgeois revolution’.

Maoists classically argued that the same ‘survivals of pre-capitalist relations of production’ mean that the prime revolutionary class is the peasantry. Just as - according to Maoists - the working class of the imperialist countries forms a labour aristocracy relative to that of the colonial countries, so the urban working class of the colonial countries forms a labour aristocracy relative to the rural exploited classes. The strategy for revolution is therefore to ‘surround the cities’. It is this strategy that the Naxalites have been attempting to apply, with very varying levels of success, in parts of India - mainly in eastern states - since the 1970s.

There are very substantial objections to the arguments both of the ‘official communists’ and of the Maoists which can fall within the same general framework of the development of capitalism out of pre-capitalist societies, and the idea that some pre-capitalist relations of production survive in ‘third world’ countries, including India.

For example, both the ‘old Bolsheviks’ of Lenin’s time and Trotsky alike argued: (a) that the capitalist class would not seek to overthrow the pre-capitalist state (because it was more afraid of the rising working class than of the declining pre-capitalist classes); and (b) that the peasantry could only play a revolutionary role if the urban proletariat took the lead. They differed as to whether contradictions between the urban proletariat and the peasantry would mean that the resulting regime would fail in the absence of immediate support from the western proletariat taking power (Trotsky) or whether a ‘democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and peasantry’ could be (relatively) stable (Lenin). But neither would have agreed with a strategic class alliance with the bourgeoisie (the line of the Russian Mensheviks) or with peasant leadership in the revolution (the line of the Russian Socialist Revolutionary Party or Narodniks).

Equally, but less immediately dependent on Russian debates, it could be argued: (c) that the global course of events since 1945 has shown that the ‘national’ or ‘democratic’ bourgeoisie is an utterly untrustworthy ally for the working class; or (d) that the Maoists’ narrative of the Chinese revolution as a guerrilla struggle based on the peasantry and ending with ‘surrounding the cities’ is false: the Chinese Red Army in the 1940s was a large regular field army controlling substantial territory and supplied with munitions by the USSR. And the Chinese Communist Party of this period, if in a sense it based itself on the peasantry, continued to recruit cadre from the urban classes.

Banaji’s objections are more fundamental than these. In ‘Ironies’ he argues that a substantial part of what the Naxalites identify as ‘peasants’ are in reality already rural proletarians. Hence the Naxalites succeed - in their base-building phases - when they build what are in substance local rural proletarian mass movements. And hence they fail - in their bids to hold onto and govern territory against the Indian state - when they try to follow the Chinese example.

In History as theory, Banaji goes further. He argues that the whole ‘traditional Marxist’ scheme of differences between modes of production which are defined by the mode of exploitation - slavery in classical antiquity, serfdom under feudalism, wage labour under capitalism - is to be rejected. This scheme is, he says at several points, “teleological” (without explaining what he means by that). The objections are backed by depth empirical research, which he claims has been lacking in many Marxist writers who support the mode of exploitation schema.

This running argument makes History as theory more than ‘selected essays’. It ties together into a single argument chapter 2, ‘Modes of production in a materialist conception of history’ (1977); chapter 3, ‘Historical arguments for a logic of deployment in pre-capitalist agriculture’ (1992); chapter 4, the previously unpublished ‘Workers before capitalism’; chapter 5, ‘The fictions of free labour’ (2003); chapter 6, ‘Agrarian history and the labour-organisation of Byzantine large estates’ (1999); chapters 7 and 8, two critiques of Chris Wickham’s Framing the early middle ages (Oxford 2005), one new and one from 2009; chapter 9, ‘Islam, the Mediterranean and the rise of capitalism’ (2007); chapter 10, ‘Capitalist domination and the small peasantry; the Deccan districts in the late 19th century’ (1977); and two new concluding chapters, 11 and 12, ‘Trajectories of accumulation or ‘transitions’ to capitalism’, and ‘Modes of production: a synthesis’.

If these arguments of Banaji’s are right, those of the Indian ‘official communists’ and Naxalites are not merely falsified in the way that Trotskyist or old Bolshevik objections would falsify them. They fall to the ground as irrelevant to reality, because based on a false a priori construction about historical development.

Overkill

At the same time, however, if the full effect is given to Banaji’s negative critique of the ‘traditional Marxist’ scheme, but no positive alternative scheme of general historical development is put in its place, Marx’s and Engels’ core arguments for the leading role of the proletariat in the struggle against capitalism also fall to the ground and for the same reason. What is left is merely an ethical or utopian socialism. This ethical or utopian socialism may prioritise the working class, as Banaji’s actual politics does. But it lacks serious and solid grounds for supposing that working class self-activity under capitalism points towards a future without capitalism. The result, in other words, is theoretical overkill.

There is a sense in which theoretical overkill is predictable from Banaji’s history. Banaji studied classics at Oxford University in the 1960s and went on to masters-level postgraduate work there before returning to India in 1972. As a student he became a member of International Socialism, the precursor of the SWP. In India, campus activism at Jahawarlal Nehru University Delhi in 1972-74 was followed by labour research and organising in Bombay in the late 1970s-80s.[4]

In the late 1980s Banaji returned to Oxford and to classics to write a doctoral thesis on the late antique agrarian economy in Egypt, presented in 1992, which was published in a revised form in 2001 as Agrarian change in late antiquity: gold, labour and aristocratic dominance (Oxford). Agrarian change, though its origins as a doctoral thesis make it tightly argued and densely documented, is plainly part of the same general project on agrarian relations and modes of production as the essays in Theory as history. Since the 90s Banaji has held a range of senior research posts in various universities.[5]

His joining IS when he was a student in the late 60s/early 70s cannot have been an ‘only show in town’ decision. Oxford University at the time had a significant Communist Party with a real intellectual life. The Healyite ‘orthodox Trotskyist’ Socialist Labour League was mainly based at the car factory, but also had a significant presence on campus. Later a mad sect, the SLL at this period intervened seriously in the academic left as well as the trade unions. The Mandelite International Marxist Group started its presence in the town at Ruskin, the trade unionists’ college, but by 1969-70 was significantly present on the university campus. The Maoist CPB (Marxist-Leninist) had a small but active branch in the city. And, of course, there were the usual recurring, ephemeral, semi-organised groups of anarchists, libertarian socialists, situationists, etc, who were and are found in every university town. The Oxford far left had various common projects in which they worked together, polemicised with each other and so on. Banaji’s choice to go with IS must have reflected not merely general radicalisation and activist commitment, but an active preference for IS over the alternatives.

The SWP is today a fairly standard ex-Trotskyist group evolving towards a sectarian left version of ‘official communism’. But in the late 1960s to very early 1970s, before the ‘Bolshevisation’ of the mid-1970s and the ‘party turn’ of 1977, the IS was something quite different. Its international politics were closer to those of today’s Alliance for Workers’ Liberty. Its ‘class struggle strategy’ for Britain and Europe was closer to that of today’s Commune group.

The IS’s origins were in a line of argument most clearly summed up in Tony Cliff’s State capitalism in Russia (1955): the argument that the USSR was a ‘state capitalist’ regime. Some other authors have suggested that ‘state capitalism’ in Russia was an extreme form of the protectionism and high-level state control common to transitions from feudalism to capitalism. For Cliff, in contrast, it was an expression of capitalist decline, a stage of monopolised capitalism beyond imperialism.[6]

This argument was - as I suggested above that Banaji’s argument in History as theory may be - theoretical overkill. The post-war ‘official’ Trotskyists, following Trotsky’s 1939-40 arguments on the partition of Poland, said that the Sovietisation of eastern Europe and the Chinese revolution was somehow ‘progressive’ (whatever the explanation). Cliff’s theory rejected this in the most categorical way possible: the regime was part of the obvious enemy, capitalism.

But to achieve this result involved identifying as ‘capitalism’ a regime without unemployment (instead there was massive make-work and low labour productivity), which suffered from endemic and episodic sectoral underproduction, not from cyclical crises of overproduction.

It also involved casually conflating capitalism with pre-capitalist modes of production and these with each other. Thus Cliff at one point in State capitalism in Russia made an analogy between the Soviet economy and those of ancient China, Egypt and Babylonia (traditionally described by Marxists as examples of the ‘Asiatic mode of production’); at another he cites state ownership of the land under the Mamluk regime as ‘Arab feudalism’, showing that class society is compatible with the absence of private property in land.[7]

New left and ‘teleology’

As well as this theoretical overkill, the IS in the late 1950s to early 1970s was deeply influenced by the ‘new left’, which emerged after the crisis in the western communist parties caused by ‘de-Stalinisation’ and the 1956 Hungarian revolution. In the 70s some ISers - notably Banaji’s slightly younger contemporary at Oxford, Alex Callinicos - were also influenced by French left-‘official communist’ theorist, Louis Althusser.[8]

The question of ‘modes of production’ was problematic for the ‘new left’ in four ways, two coming from ‘official communism’ and two from the western academy. The first was that ‘official communist’ doctrine justified the tyrannical character of the Soviet and similar regimes as a regrettable necessary stage in the transition from capitalism to communism proper. The second was that this doctrine was also used to justify further ‘necessary stages’: the ‘advanced democracy’ which was supposed to be the outcome of the ‘anti-monopoly alliance’ in the imperialist countries, and the necessary capitalist stage in the colonised/neo-colonised countries.

The third problem was the great emphasis placed on the supposedly teleological character of Marx’s account of history by Karl Popper and a broad range of sub-Popperian authors across several academic disciplines: authors who built on Max Weber’s ‘ideal types’, opponents of ‘historicism’ in anthropology, and so on.[9] The fourth was the US state funding of social democratic politicians and authors in the cold war period. This meant - for example - widespread willingness to deploy Karl Kautsky’s theoretical objections to the ‘prematurity’ of the Russian Revolution, based on a theory of necessary stages, in favour of the idea of ‘Leninism opposed to Marxism’.

‘New left’ authors and the activists who used their ideas responded in two ways. One - as it were the right wing of the ‘new left’ - could perhaps be called ‘premature Eurocommunists’. ‘Marxist humanists’ like Roger Garaudy in France and EP Thompson in England called on the ethical and humanistic elements of the writings of the early Marx against the ‘scientism’ of the later Marx, Engels, Kautsky and Stalin. They accepted the general frame of capitalist constitutionalism as protecting important liberties that Stalinism destroyed; and they retained the general political framework of the people’s front policy, merely getting rid of the ‘inhuman’ role of the party.

The second line of approach was to resurrect the arguments of the revolutionary syndicalist, Georges Sorel, in The decomposition of Marxism (1908) - for the most part not directly. Rather the arguments used were those of authors within the socialist movement, but to some extent influenced by the revolutionary syndicalists, like Anton Pannekoek; and authors from the left wing of the early Comintern, like Karl Korsch and (in the early 1920s) Georg Lukács and Antonio Gramsci. Rosa Luxemburg, viewed pretty much exclusively through the prism of Reform or revolution (1900) and The mass strike, the political party and the trade unions (1906) became almost the totem of this sort of ‘new left’.

This trend’s political inheritance from Sorel was a syndicalist focus on the immediate class struggle at the point of production - strikes, and if possible unofficial ones. Its theoretical inheritance was the belief that the ‘historical materialist’ arguments shared by the young Marx and Engels (and, in reality, by the late Marx and Engels) could be discarded. The centre of Marxism was Capital and, in particular, the Hegelian dialectical exposition of the first part of volume 1 of Capital. These arguments provided the exclusive ground for the leading role of the working class and could be read to give a central role to the strike as the moment at which the working class, otherwise merely within capitalism, became an actor against it.

The ideas of this ‘left new left’ could be mixed up with elements taken from Maoism or from Che Guevara. By the late 1960s it had also had a profound influence not only on the IS, but also on the ‘official’ Trotskyist Unified Secretariat of the Fourth International. The ‘orthodox’ Trotskyist opponents of this influence, in so far as they did not collapse simply into ‘official communism’ (the US SWP, and so on) have since then largely collapsed into it themselves. It has thus shaped the ideas of the far left well beyond people who are conscious of its origins.

Louis Althusser was a left academic within the Parti Communiste Français somewhat sympathetic to Maoism, who deployed a highly selective version of the ‘left new left’ critique of historicism and ‘historical materialism’ to provide arguments against the PCF’s ‘Marxist humanist’ critics. Althusser in a certain sense preserved the idea of distinct modes of production, but he did so by effecting a complete severance between modes of production, which cease to form a general historical narrative. Rather Althusser adapted the ‘structural anthropology’ of Claude Lévi-Strauss, itself derived from the ‘structural linguistics’ of Ferdinand Saussure. The key move was that ‘synchrony’ (structural causation within a mode of production) overdetermines ‘diachrony’ (historical development). Like the ‘left new lefts’ Althusser insists that the only real Marxism is that of Capital, claiming that an ‘epistemological break’ lay between the early Marx and the Marx of Capital.

The intellectual context within which Banaji constructed his early arguments was thus one in which it was an orthodoxy not needing much explanation that the ‘Stalinist’, ‘Kautskyite’ or ‘Engelsian’ sequence of modes of production (primitive communism, Asiatic mode, slavery, feudalism, capitalism, communism in a higher form) was wrong, teleological, deterministic-automatistic, and so on, and that Marxism had to start from Capital Vol 1 and nowhere else.

Within this framework, references to ‘modes of production’ have to be read not as phases of a narrative, but as ‘ideal types’ in the style of Max Weber: or, to put it another way, as a historian’s equivalent of the ‘comparative statics’ which are foundational in the various forms of marginalist economics.

These assumptions remain present in Banaji’s work down to the present day as assumptions, not argued positions. What his work does is to offer empirical historical evidence, informed by economic analysis, against authors and tendencies who do use the sequence of modes of production in historical and political argument.

True or false?

What I have said so far perhaps helps to explain why Banaji’s arguments have taken the shape they have. But it certainly does not prove they are false. On the contrary, the essays are very high-quality historical work.

It seems to me that Banaji succeeds in demonstrating certain of his specific claims. In particular:

1. There was very substantial use of wage labour in agriculture (and elsewhere) in many pre-modern societies. (Chapters 3, 4 and 6).

2. There is a spectrum between the considerable degree of freedom (of movement, of choice of employer, etc) of many workers in the more developed capitalist countries and the total unfreedom of chattel slaves. Neither the chattel slavery of Africans in the early modern to 19th century plantation economies nor forms of indentured labour, debt-bondage, sharecropping and so on, then or more recently, can be said to show the existence of (in any strong sense) pre-capitalist social relations of production in a country (chapter 5).

3. Following the last two points, phenomena of labour relations at the point of production alone cannot be used to identify the mode of production in the larger sense or to describe the larger society as pre-capitalist (passim in the book).

4. Following on from all this, the ‘Brenner thesis’ that capitalism emerged in England as a result of a specific mutation in labour relations in agriculture is to be rejected. Rather capitalism, at least in its modern sense, emerged in the later middle ages in the Mediterranean interface of Catholic Christendom, Byzantium and the Dar al-Islam (chapter 9).

5. Indian agriculture in the 19th century was dominated by capitalist relations, although these were mainly ones of (in Marx’s terminology) the formal subsumption of labour under capital (household commodity production dependent on and organised by merchants and moneylenders) rather than ones of the real subsumption of labour under capital (large-scale shipping, factory production and mechanised or semi-mechanised large-scale farming).

Any narrative of historical materialism will therefore have to take serious account of Banaji’s arguments and evidence on these issues.

On the other hand, a number of Banaji’s assumptions, and in some cases his formal claims, are more problematic. It will clarify what follows to state some points as briefly as possible. A second part of this review will provide more supporting argument for some of these points.

First and at the most superficial level, it seems to me that the line of argument connecting reformism and Stalinism to historical materialist ‘automatism’, ‘scientism’, etc is false as a characterisation of the history of the workers’ movement and leads to dead-end politics. I have made this argument elsewhere and will not elaborate further here, since, though I think it is part of the background to Banaji’s argument, it is not part of the argument itself.[10]

Second. The argument that the idea of the sequence of modes of production is ‘teleological’ is unsound as a matter of epistemology and historical method, quite irrespective of whether the sequence of historical periods constructed is a Marxist, or any other, interpretation of history.

What we actually have from Marx and Engels on this topic are a few general sketches of the approach (in The German ideology, the Communist manifesto, the Contribution to the critique of political economy); some of Marx’s rough notes; a polemic by Engels against the rival ‘force theory’ (in the Anti-Dühring); Engels’ Origin of the family based on the contemporary anthropology and on aspects of classical antiquity; and some journalism and private correspondence. This material was all written before the publication of the vast bulk of the written sources for ancient and medieval society now available, let alone the information generated by archaeology. To treat Marx’s and Engels’ comments as holy writ for modern historical investigation is therefore obvious nonsense.

There are, however, solid non-historical grounds in human biological nature and our material needs for the core of historical materialism - that the ways in which historical societies produce their material subsistence constrain the sort of general social orders possible. Similar grounds support the rejection of methodological individualism (humans are a social species) and of marginalism (there are physical minimum subsistence levels, maximum working hours and maximum quantities of land). These grounds require the analysis of societies and their dynamics in terms of the social division of labour.

The productive character of this basic approach as a research paradigm in history is evident in historical work produced in the last century (Banaji’s work is a very distinguished example). This evidence also suggests that certain aspects of Marx’s and Engels’ specific arguments and comments on aspects of the past were insightful beyond the historical evidence available to them. But we have to be willing to reconstruct their specific theories and narratives very radically or replace them, so far as this is required by the evidence.[11] The question is whether reconstruction on this sort of basis will produce similar arguments to those of Theory as history.

Origins of the present

Third. Because of his assumptions about teleology and so on, Banaji simply does not address in any systematic way the problems of grand-scale narrative of the origins of the present and of historical periodisation and transitions. Nor, apart from in the very concrete chapter 9 on the Mediterranean origins of capitalism, does he address the specific aspect of this problem which presents itself as the historical, economic and social-scientific debates about the origins of European priority in the development of capitalist modernity.

The result is that the most theoretical sections of the book - chapters 1 and 2, 10 and 11 - are relatively disappointing: their outcome seems to be merely negative critique, and fiddling round the edges of the classical Marxist scheme.

There is no engagement with the attempts at a general reconstruction by authors coming from the Marxist tradition, like - for example - Igor Diakonoff’s The paths of history (1999) or David Laibman’s Deep history (2006). Nor are fully non-Marxist attempts to address these issues tackled, like - for example - John A Hall’s Powers and liberties (1986), or Michael Mann’s Sources of social power (1986-93). There is also a large volume of neoclassical and ‘institutionalist’ economists’ writing on history from marginalist perspectives - much worthless, but some containing real insights - produced since the 1980s.

Fourth. This ‘missing link’ affects the plausibility of some of the interpretations in History as theory: in particular, the two chapters of critique of Chris Wickham on the early middle ages (chapters 7 and 8).

The starting point here is a persistent controversy between ‘modernist’ interpretations of the economy of the Roman empire (and, in particular, the late empire), which stress its similarities to European capitalism in the period before steam-driven industry, and ‘primitivist’ interpretations, which stress its differences.

Fashions among ancient historians have shifted on this topic. In the 19th century the ‘modernist’ view was largely dominant. In the 20th, the dominant interpretation shifted towards the ‘primitivist’ side. In the very recent past there has been a shift back towards ‘modernism’. Banaji places himself on the ‘modernist’ side of this dispute, while he argues that Wickham’s theoretical construction assumes ‘primitivism’.

The shifting fashions have an ideological aspect. But the absence of a clear, settled view is also partly due to the severe limitations of the historical sources for the shape of the Mediterranean and European economies before the central middle ages, when tax and judicial records, etc begin to survive in sufficient quantities to be plausibly representative.

In addition, the sources we do have may be analogous to the words linguists call ‘false friends’, where the same word is used in two languages with different meanings. The reason for this is that (as Marx observed in The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte) Europeans down to the 19th century were very prone to ‘copying’ classical antiquity. Words and forms may therefore be the same in appearance, but very different in content when read in context.

This is intensely true of legal sources. The same limited body of Roman legal texts was read from the 11th-12th century down to the 18th as the basis for medieval law; from the 16th-19th century as the basis for overthrowing medieval law in order to ‘return’ to an imagined ‘law of business Rome’ - ie, create law fit for capitalism; and from the 19th onward as evidence for scholarly interpretations of the Roman society and economy, whether ‘modernist’ or ‘primitivist’.

Hence, legal sources cannot be read as transparently expressing current economic practices. This is not only true of legislation and treatises, but also of written contracts and pleadings in disputes before judges: these documents are products intended to create legal results, and therefore using the language of the law, even if this language refers to long-obsolete practices or involves fictions. Using them as evidence for the social relations of production requires an interpretive context which includes the structure and evolution of the legal order as a whole - which, of course, poses that of the evolution of the social order as a whole - in order to disentangle norm and practice.

In Agrarian change in late antiquity Banaji’s use of legal sources is able to approach success in this task, because the main body of the work is narrowly focused on the specific evolution of the Egyptian agrarian economy in antiquity - which was always a special case and is much better evidenced than elsewhere. In the critiques of Wickham, which necessarily have a broader focus, some of the arguments are more problematic.

This is also, I think, because the underlying structure of Banaji’s negative critique of the relation between mode of production and mode of exploitation in History as theory, and his non-engagement with the larger ‘origins of the present’ issues, does not really allow for full integration of the questions of the evolution of legal norms.

Fifth. By the rejection of ‘teleology’ and so on, Banaji rules out in principle the interpretation of particular forms as transitional. He makes the superficially legitimate point that there is a risk that the ‘transitions’ will swallow up the ‘mode of production’. However, arguably we should read ‘modes of production’ as forms of social dynamics which rise and decline, and which only have strong direct descriptive value at the moment of apogee. (This moment should be placed for feudalism somewhere around the 11th-13th centuries; for classical antiquity somewhere before the fall of the Roman republic; for capitalism - probably - in the 19th century.)

If so, the transitional forms will include not only forms which are visible precursors of a new order, but also specific adaptations to decline which do not foreshadow the new, and blind-alley experiments which fail.

This point has more specific political implications. The formal subsumption of labour under capital in Marx’s writing is transitional between household production and capitalism proper. It is empirically observable that it does not in itself produce the same political dynamics as the real subsumption of labour under capital. This is because only the real subsumption of labour under capital forces labour to recognise that it is engaged in a cooperative enterprise which is part of a general social division of labour. The implication of this observation is not that Banaji’s critique of Indian Maoism and ‘official communism’ is exactly false, but that, in positing simple labour self-organising as the alternative to these trends, it is not merely theoretical overkill, but also may fail to address issues that need to be addressed.

I will elaborate on some of these points in the second part of the review.

mike.macnair@weeklyworker.org.uk

Notes

- www.outlookindia.com/article.aspx?264738

- The Hindu April 22 2010 (www.hindu.com/2010/04/22/stories/2010042263141100.htm); Wall Street Journal November 30 2010 (blogs.wsj.com/indiarealtime/2010/11/30/does-criticizing-india-count-as-sedition-arundhati-roy-will-find-out).

- kafila.org/2010/03/22/response-to-arundhati-roy-jairus-banaji. Representative criticisms can be seen in the comments to the original post, but there is a lot more debate elsewhere on the web.

- ‘Interview with Jairus Banaji’ in the Sri Lankan online magazine Lines 2006: issues.lines-magazine.org/Art_May06_Aug06/jairus_short.htm

- From the preface to Agrarian change and from various university websites.

- This as well as earlier documents by Cliff are available on the Marxists Internet Archive at www.marxists.org/archive/cliff/index.htm

- Chapter 6: www.marxists.org/archive/cliff/works/1955/statecap/ch06.htm#s6; Appendix: www.marxists.org/archive/cliff/works/1955/statecap/appendix.htm#s4

- A Callinicos, Athusser’s Marxism London 1976.

- István Mészáros in The power of ideology (London 1989) critiques authors of the first type. Rosalind Coward deploys the second type in Patriarchal precedents (London 1983) to provide Eurocommunist arguments against Marxism.

- Mainly in Revolutionary strategy (London 2008), but also in various articles in this paper.

- I argued in ‘Darwinism and Marxism’ (Weekly Worker December 19 2002) that Steven Jay Gould’s The structure of evolutionary theory (2002) was a good guide to the sort of method involved.

some regimes are nothing more than “tigers of paper” and that their citizens are capable of overthrowing them

| A Springtime of the Arab Peoples? |

| [2011-02-01 ] |

By Daniel Atzori In 1848, a series of revolutions, popularly known as the “Springtime of the People”, spread all over Europe. Political upheavals threatened, and in some cases overthrew, European regimes seen as unjust and repressive by their subjects, who wanted to become citizens. From France to Poland, from Denmark to Sicily, “a spectre was haunting Europe”, as Marx famously wrote. Is the Tunisian uprising the beginning of a new revolutionary wave, which will spread all over the Middle East and North Africa? First of all, the Tunisian upheaval is challenging the prejudice according to which Arab states are strong, while Arabs are like children, not mature enough to rule themselves democratically and to hold their governments accountable. Orientalist scholarship adds the prejudice that Arabs are inherently passive and fatalistic, and thus authoritarianism is the only form of government suitable for them. But the Tunisian youth rose up and threw these misconceptions into the dustbin of history. Many Arabs tend to consider their regimes unjust, and sometimes oppressive, but they do not dare to claim their rights out of sheer fear. The Tunisian revolt seems to show that some regimes are nothing more than “tigers of paper” and that their citizens are capable of overthrowing them. Nazih Ayubi entitled one his most influential book “Overstating the Arab State”, explaining that “the real power, efficacy and significance of this state might have been overestimated. The Arab state is not a natural growth of its own socio-economic history or its own cultural and intellectual tradition. It is a ‘fierce’ state that has frequently to resort to raw coercion in order to preserve itself, but it is not a ‘strong’ state.” Ayubi is telling us that the very fact that several Arab regimes easily resort to violence against their own citizens, arresting and torturing potential opponents is not a sign of strength, but of extreme weakness. Does this look like a paradox? According to Machiavelli, the state can be represented as a Centaur, a mythological creature that is half human and half beast. Based on this intuition, the XX century Italian political theorist Antonio Gramsci analysed how the power of the state is composed by both consensus (the human side) and violence (the beast). Gramsci was writing while he was a political prisoner during the Fascist period: he had direct experience of an unjust regime that tortured and ultimately killed his body but was powerless against his thought. A revolutionary thought that gave strength and energy to those brave Italians who, after his death, overthrew the Fascist regime once and for all. According to Gramsci, the state achieves consensus through media, schools, universities, while it coerces through police, army and secret services. In order for a state to exist and maintain itself, there should be a balance between these two dimensions. States that survive merely relying on violence and coercion are intrinsically weak and doomed to fall, because the ruling class does not enjoy any true hegemony over the ruled masses. Does this sound abstract? Let’s have a look at the Soviet Union. Loads of Westerners, but also most of Soviet citizens, considered the Soviet Union to be almighty and unbreakable. But the Soviet Union did break down. The all-powerful secret police and the army were just a veil, behind which the Emperor was naked. The Soviet Union could only rely on its police, army, secret services, prisons and concentration camps: but there was not much behind that. The regime was lacking consensus: it was an idol with feet of clay, which one day just crumbled down. The Soviet regime could almost only rely on its “armour of coercion”, in Gramsci’s words: but there was nothing behind that armour. The Tunisian example shows us that once the front line is conquered, the battle is over, because the “army’ of the regime does not have strategic depth, since it does not enjoy consensus. Once the Tunisian people started their offensive, the very pillars of the regime started shaking. The footages of the Tunisian policemen joining the protesters show how weak and vulnerable the regime really was. Several Arab regimes are understandably worried for the consequences of the Tunisian upheavals. They have now two options. The first is to increase the level of repression in order to prevent revolutionary outcomes. In the short term, this solution may work. But this will further erode their consensus, feeding the anger of the Arab street. Revolutionary waves may become more frequent, and more likely to succeed. Moreover, terrorists will try to take advantage of the malaise, hypocritically claiming to represent the masses. Unequal taxations, which squeeze the poor and forget the rich, will further fund the repressive machinery, instead of being invested in social and economic development, first of all by decreasing the astonishing rich-poor gaps. The second option is to really reform Arab societies, empowering the citizens and allowing diverse political actors to participate. When people would be treated as citizens, and not as subjects, Arab states will become truly representative, and thus stronger. It is when the Centaur will show his human face that a peaceful springtime of the Arabs will really blossom. |

Derrida

An Irishman's Diary

http://www.irishtimes.com/newspaper/opinion/2011/0125/1224288229922.htmlEAMON MAHER

SINCE his death in 2004, the reputation of the philosopher/theorist, Jacques Derrida, whose name is synonymous with “deconstruction”, has gone from strength to strength. A man of immense intellect and boundless energy – his publications output of more than 70 books is nothing short of remarkable – he never attained the type of respect among the French academic establishment that he enjoyed in the United States, where “French theory” became a growth industry in university campuses from the 1970s onwards.

His ostracism in France may have had something to do with the fact that his approach was very far removed from the traditional discourse that the French system demands. Also, he is a figure whom it is difficult to situate in intellectual terms: was he a philosopher or a literary critic? In a sense he was neither and both. Impossible to classify, he inspired suspicion and adoration in equal measure. Benoît Peeters’s biography, simply entitled Derrida , published by Flammarion, is the first to be published since the author’s death.

Peeters is conscious of the magnitude of his task: after all, Derrida was one of the most influential thinkers of the 20th century. Although the biography contains 740 pages, one has the impression that it could have been a lot longer, so rich was the life and the work of this exceptional thinker. Also, the biographer was keenly aware of the wariness displayed by Derrida towards biography: in one of his conference papers, for example, he cited the following comment of Heidegger in relation to Aristotle: “He was born, he thought, he died”. All the rest was just anecdotal, in Derrida’s view. However, Peeters states that writing the life of Derrida means telling the story of a Jew from Algeria, who was (temporarily) banned from school at 12 years of age and subsequently became the most translated French philosopher of all time. It means coming to grips with a complex, tormented man who always felt like an interloper in the French university system. There is something unique about the capacity of the pied-noirs , the French colonists in Algeria, to view French society through the eyes of the “outsider”. Small wonder, then, given his origins, that the “Other” forms such an important part of Derrida’s philosophy.

Generations of Irish third-level students from the 1970s onwards were exposed to the ideas of French theory in faculties as diverse as sociology, anthropology, English and, of course, French. It challenged them to question the traditional trust placed in language to convey meaning. It also taught them to question “givens” and to deconstruct myths that are often treated as reality. In the current crisis we are undergoing, such skills could prove invaluable.

From the time he came to Paris to attend the Lycée Louis-le-Grand in 1949 to his death in 2004, Derrida was at the centre of some of the most seismic events in world history. He would be accepted into the École Normale Supérieure in 1952, which marked the beginning of a long association with the venerable rue d’Ulm institution as a student and professor. Louis Althusser was a close friend and colleague, but he was also close to the writers Jean Genet and Hélène Cixous.

Paul de Man was the person responsible for establishing and spreading his reputation in America, where he would spend a lot of time giving seminars and serving as visiting professor in various prestigious institutions. With other philosophers such as Maurice Blanchot, Michel Foucault, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Jacques Lacan, Paul Ricoeur and Jürgen Habermas, his relations were marked by controversy and the occasional bitter exchange. Life in academe is not renowned for its serenity, but some of what is described by Peeters is nothing short of vicious.

The Algerian war preoccupied Derrida, as it did Camus, another pied-noir , and his family had to move to France to escape the atrocities that preceded independence. He lived through the turmoil of May ’68 and had a lifelong association with leftist politics without ever aligning himself definitively to communism or socialism. He was shocked by the repercussions caused by 9/11 and visited New York shortly afterwards. He was totally committed to his students, whose work he always corrected with care and whose careers he promoted zealously. Shortly before his death, it was strongly rumoured that he would be awarded the Nobel prize, but it was just one more honour that escaped him.

Reading this biography, one’s respect for Derrida grows as one discovers the human side behind the public persona. He was a child of the Mediterranean who experienced rejection on numerous occasions because of his “otherness”. He suffered from sporadic depression, and had one well-publicised romantic entanglement that caused great pain to him and those close to him. He knew all about alienation and, while he was capable of vindictiveness, he was also prepared to mend bridges and start afresh. All in all, Peeters’ work shows us a new dimension of Derrida and makes the man, if not his work, less impenetrable.

Sunday, January 30, 2011

My article in defense of Chinese revolution

“Up the Yangtze” premiered two years ago on PBS’s independent documentary program “POV”. This month it is back in circulation on the digital channel PBS World. The week of the US-China Washington DC Summit it was repeated several times.

“Up the Yangtze” claims to be a portrait of the profound social changes taking place on the banks of China’s mighty Yangtze River. The river is being altered dramatically with the construction of the Three Gorges Dam, built to end millenia of devastating floods. It will also provide 10% of the country’s electricity supply. 2 million people and several modern cities have been relocated as construction proceeded.

Such a massive project is unthinkable in a capitalist country like the United States. Here strategic planning is left to the Pentagon and Wall Street’s pragmatic seers only approve public projects if the bondholders get paid first. A project to insure energy and development over hundreds of years is unthinkable. In China, where basic industry and foreign trade were nationalized after the 1949 revolution, other priorities that quarterly profits still exist. As the TV news experts from Sean Hannity to Charlie Rose never tire of telling us, it is a communist country.

The documentary has a not very independent agenda. This is to discredit the Three Gorges Project and trash the historic conquests and current stage of the Chinese socialist revolution, portraying it as a system worse than capitalism. This is done with a slanted depiction of the experiences of 16 year old Yu Shui. With her parents and siblings, she lives in a shack made of scrap on the banks of the rising river. Just graduated from middle school, her parents force her to leave home and start working on one of the luxurious ocean-scale cruise ships that ply the river, loaded with haughty and insufferable Western tourists. Like most young people around the world today, she must find work to support her family.

“Up the Yangtze” visits no other homes or apartments along the river; we are clearly led to believe that shacks made of scrap wood are the norm. We are also led to believe that parents who grew to adulthood in the 1960s during China’s Cultural Revolution remain illiterate and incapable of managing the most basic requirements of life. Among many other positive political and cultural conquests of the Cultural Revolution was the goal of universal literacy. Somehow the Yu parents missed this effort, and there is no explanation for it. There is also no explanation for why they live a marginal existence eating only meager crops from the the plot of land they laid claim to. Are they farmers? Are they simply irreconcilable and anti-social contrarians? After an hour of viewing, it is easy to see that we are not being given all the facts. In place of facts, we have endless cut-aways to the family’s scrawny and filthy kitten navigating through the mud of their house. Such editorial choices carry their own message: life for the ordinary Chinese is intolerable.

Yu Shui’s probationary employment on the river cruise ship is the most interesting part of the film. One might think that a young woman put to work running an industrial dishwasher and weeping openly as she adjusts to hard work and homesickness is the stuff of tragedy. But despite the filmmakers’ intentions, the opposite is true. Yu Shui, in leaving her family’s squalid rural existence behind, liberates herself as she becomes a member of China’s growing working class. She becomes more confident, more mature, and carries herself with pride as she accepts higher levels of responsibility on the job. The most fascinating scene in the movie occurs as this evolution proceeds; Yu Shui’s co-workers meet in their bunks to honestly discuss her strengths and weaknesses, and the ways in which they may be able to help her. This concrete and splendid class solidarity would be unknown in most U.S. workplaces, where boss-inspired gossip and suspicions are the law of the jungle.

Contrasted with Yu Shui is 19 year old Chen Bo Yu. Chen’s parents have a higher income than Yu’s, and unlike Yu he is an only child. While at first he seems to be making an easier transition to life aboard the cruise ship, youthful arrogance and inability to learn his job lead to firing at the end of the probation period. So here we have another lesson: China’s one-child policy had bred a spoiled and stunted generation.

Life aboard a cruise ship catering to tourists from Europe and North America has its humiliating and absurd ordeals. All employees are given Western names and taught English so they can - as their trainer tells them - compete in the 21st century job market. New employees in orientation are told to refer to fat customers as “plump,” and are told not to mention politics. Among other off-limits topics of conversation: Quebec independence and the Irish freedom struggle. With pleasure the viewer imagines what must have occurred between guests and servers on earlier cruises to make these rules necessary.